Abattoir Bratislava - Cillian O'Neill

Abattoir Bratislava - Cillian O'NeillSince ACT is about making a change, we need to talk about impact. We must learn about the sorts of impact art can make, about the role and place of impact in art practices, and about how art practices themselves are impacted, for instance by Covid-19.

Therefore, as part of the Learning to Impact Work Package of the ACT project, we research the many faces of impact. We do so by interviewing artists. With The Interview Series we tap into their embodied, concrete artistic practices. We want to build an understanding of how these practices (may) evolve in the face of the current challenges. How the artists learn to ‘stay with the trouble’. How the urgency of climate change, ecology and biodiversity informs their attitude towards the social impact of their artistic work.

Sarah Vanhee’s interdisciplinary work travels inbetween civil spaces and institutional art fields. She worked in open fields, prisons, private living rooms, theatres, on public canvases, in corporate meeting rooms, etc. She sees public space as a forum for the exchange of repressed or underexposed knowledge. This perspective is explored and realized in her work and research. While strongly embedded locally, Vanhee’s work has been presented internationally in diverse contexts. Jacco van Uden & Arie Lengkeek talk with Sarah:

‘I cannot imagine ecological or climate justice without social justice. I am interested in ecology in the sense that i’m interested in perceiving the world as an interconnected web of things and people. I’m less interested in ecology when it comes to moralism. because I believe it doesn’t work, it turns people away… It is alienating.’

What does concept of ecology this mean for your work?

Ecology has everything to do with connections. Discovering, exploring, acknowleding, re-establishing them. The so-called covid-crisis is, amongst others, a crisis of interconnectedness. A testimony of the non-acknowledgment that we live in an interconnected, global world. We got that presented in a very literal way, it also became a crisis of human interconnectedness. Art, can play a role in making these connections apparent.

Then, what becomes apparent, audible, visible?

There’s a sociologist, Rob Nixon, who introduces the term ‘slow violence’. It is opposite to the spectacular forms of violence, like 9/11, a very phallic, male dominant visible form of violence. Slow violence are the oil spills, violence wrought by droughts and climate change, by deforestation, by nuclear poisoning. Think of disasters like Bhopal or Agent Orange. It is taking place in areas that are completely underprivileged, and because these forms of violence are indirect and slow, they are hard to visualize and it’s hard to mobilize people for justice. He sees for artists and writers an important role, to visualize and write these narratives. So we can perceive them. I find that an interesting stance. My work has a lot to do with making audible what tends not te be audible, and trying to make visible what is not visible.

How does your work move between art and activism?

I rather have a radically constructive approach to things, I must say. I prefer to not be busy with trying to relate to what I actually don’t want to relate to. For me, already at the beginning of my path as artist, I was honestly feeling bad when I would attend conferences, seminars; the continuous ranting about how bad capitalism is for us, etcetera. A lot of critique, a little use of the imagination and the capacity to act that artists actually have.

So I’m very sensitive for situations, where the same problematics as in the macro story are present. When I feel that there are tendenses for patriarchal power structures, top down, where the human element is completely absent, I’m very suspicious, I feel hesitant and don’t want to involve myself.

But I could not find myself in that critique-without-proposing. And I also think very personally: the joy, which is an important element in creation… well, my joy really lies in creating and not in critiquing. It doesn’t mean that i’m not critical, but I believe it’s much more generative to create.

What would ‘impact’ mean for this generative approach to art?

If ‘impact’ means: addressing a potential for transformation. I think of ‘Lecture For Every One’ for instance, a work that played an important role for me. It came from a wish to have a direct impact. It’s a radical example, that came from my frustration with the art world. In the ‘white cube’ of the museum or the ‘black box’ of the theatre we express critique on contemporary society, but basically everybody who sits there already agrees. I felt misplaced there. That’s not where I want to be, also not who I am as a citizen in the world. I’d like to speak with people who I maybe totally disagree with, whith people from very different backgrounds. I actually believe, that, much more than we think, we can connect through conversation and through exchange. So, from that experience, I decided that I would make a 15’ minute lecture, that is called ‘Lecture For Every One’, that could be said to every – one, in two words, every single person. I wanted to say that in environments that are potentially hostile to what I was saying. I asked the theatres who booked my work to organise the lecture as a ‘guerilla performance’. We looked for instances where people were already gathered together: a board meeting, an HR meeting in an enterprise, a choir rehearsal, a football training. Moments where people were together in a certain group, in a certain concentration, and I would interrupt this meeting, and give my Lecture For Every One. Always with one accomplice in the group, for the rest it was a totally unexpected intrusion of the agenda or programme of their meeting.

What happens, when you say this ‘Lecture For Every One’?

Very often, when I left, they could not continue with the formal agenda, they felt like they cannot go on. So the conversation would go somewhere else. We did the lecture always in the language of the meeting, so it exists in 14 different languages, we did it in 12 different countries, more than 300 meetings, more than 8.000 people got to hear this lecture. And I give this as an example because this really came from a wish from me to have a direct impact. It’s always exactly the same text, in the text I articulate that: the same words for every one, because I want to believe that it’s possible to speak to every one in the same words, in a language that is not advertising of mainstream media. I didn’t want it to be a very clear political pamphlet, it is a collection of questions, stories, statements, jokes, so the whole text is really meandering, is not explicit about what it wants, but it does ask difficult questions about what kind of society are we co-creating? And it considers every one as a co-creator of that society. That’s how every one is spoken to, that’s what every one is invited to.

Is this conviction also the foundation of your current work, ‘bodies of knowledge’ (BOK)?

I visited the indigenous countryside in Mexico in 2018 and coming back to Brussels I was thinking, how can I look at the city as a site of not only consumption and exploitation. How can I look at it as a site of richness, something generative. And then I looked at all the people being present there, with all their experiences, histories, connections: and that’s usually not how you perceive the city. I thought: if i can do something, to adress the city as place of richness, in terms of knowledge that would be also a way for me to connect to the city differently, in a radically constructive way.

With BOK our main work, as a collective, is: being on the streets, on the square, in the park with people. We call it a ‘nomadic classroom’, a tent that looks quite shabby and unpretentious. And that’s important: it looks very easy to access, both in a technical and aesthetic manner. We are easy to connect with, as we are there; we are with many and in different languages, different bodies. Most of the time and most of the resources goes into us being with people.

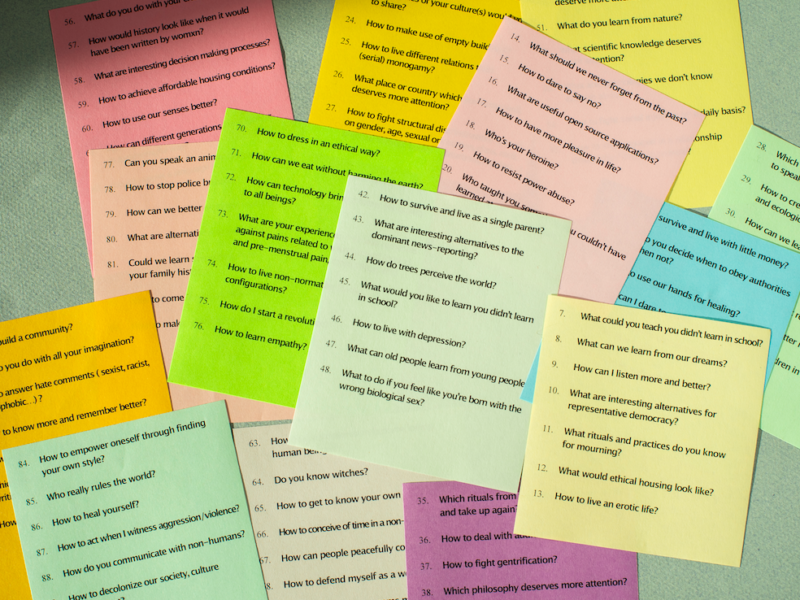

We are nomadic, we settle down at a place for about three months. There, we first of all speak with people who are not used to take the floor in public, who don’t even always assume that they know something! So, we developed tools to sense what knowledge could be present in that person. We start a conversation on the basis of questions that we have, to understand that there’s maybe a knowledge that someone could share, that would be interesting. We developed very precise tools for this. One is a learning book, with questions like: ‘what is a moment of learning you will never forget?’ ‘what would you like to unlearn?’ ‘who is a person you think we should listen to?’. We have 100 questions that we think could lead to knowledge that could create a curriculum for a school that could potentially contribute to a transformation of society.

How does BOK evolve, from these simple questions to this potential of transformation?

BOK started as an initiative by me, its now run by a collective of people, and people inscribe themselves in the project in different ways, so it becomes also a platform and a tool that people can use. It’s really not about me – I’m not a director in that sense. Flore Herman and me just wrote a text about listening, where I wrote about how to make yourself disappear from your work, yes… It’s the people that make the work. It’s not that they are part of a programme. They make the work and they become part of this network, and they come back, sometimes as listeners, or proposing something else. They are the bodies of knowledge!

With BOK, we work with a lot of people, but we also work with a kind of collective of people. The way we organize ourselves resonates in the way that we work with the people, and how we communicate. There’s this French word, Bienveillance, it has someting to do with care. Trying to take care. For us it is very important: above all e are there to listen, to take care. And it’s also something we try to do to each other. It takes a lot of time, time that is invested in relations. It’s very unspectacular, actually.

Maybe unspectacular: but maybe also a sort of ‘slow transition’, opposed to the ‘slow violence’ you mentioned before?

What develops, is an ecology of relations, also very literally. Something happens beyond the blindness of the white middleclass to which I also belong. We wonder why the ecological movement remains so white?! Of course it’s because the topics that are at the table are completely out of reach for people from more precarious classes. But at the same time, a lot of ecological solutions come already from them! For instance we had someone in the tent who spoke about ‘how to get by with very little money?’- and then you realize a lot of these solutions are deeply ecological, but she just doesn’t call them that way.

Personally also, I’m really learning from people and collectives who already for long understood that they will never be supported by dominant society. For me, they have really developed very interesting ways of organising themselves that I think are just much more interesting. That’s not a personal preference, it’s a political choice.

Follow Sarah’s work via www.sarahvanhee.com

BOK is currently in Brussels, on Jacques Brel Square, untill 11.12.2021, www.bodiesofknowledge.be

Further reading: this essay learning as movement by Silvia Bottiroli, reflecting on BOK.

This is the fourth article in The Interview Series on Impact.